Simona Kustec Lipicer*

Andrija Henjak**

1.1. Main Characteristics of the Slovenian Party System

1Slovenia is a country without a long tradition of statehood. It has had its current borders since 1945, when it was constituted as a federal republic of the socialist Yugoslavia. Slovenia became independent at the same time as it transformed into a democracy: with the collapse of communism and disintegration of Yugoslavia in 1991. As the most developed of Yugoslav republics – with the most advanced economy, already well integrated in the West European markets, and ethnically the most homogenous of the former Yugoslav federal republics – the Slovenian transition to democracy was both smooth and quick. The process was only interrupted by a brief but intense war at the end of June 1991, resulting from the intervention of the federal army, which tried to prevent the inevitable process of the Yugoslav breakup.1 Like in other post-socialist countries, political parties in Slovenia played a crucial role as proponents of change in the transition process from the former communist regime, which has been labelled as transplaced2 or ruptforma3 form of transition. The Slovenian transition was characterised by the cooperation and bargaining between the emerging civil society and new social movements, newly emerging opposition political parties, and existing political elites.4 As assessed by Fink-Hafner,5 political parties became the agents of the formation of the Slovenian state,6 but they were also shaped by this process. Some new parties emerged from the transformation of the League of Communists of Slovenia (in 1993 renamed as the United List of Social Democrats, and in 2005 as Social Democrats); the League of Socialist Youth (later the Liberal Democracy of Slovenia); the Socialist League of the Working People (later renamed as the Socialist Alliance); and the Social Democratic League (later renamed as the Social Democratic Party of Slovenia). Simultaneously the opposition to the old regime, emerging from the society, first called the Alliance of Intellectuals and later renamed as the Slovenian Democratic Alliance/Union, was established at the end of the 1980s. Since then it has served as a base for the foundation of a number of political parties. It included social groups with specific issues at heart, such as religious groups (Slovenian Christian Democrats; Christian Socialists), peasants (the Slovenian Peasant Party - People’s Party, later renamed as the Slovenian People’s Party), pensioners (the Democratic Party of Pensioners), regional parties (e.g. the Alliance of Haloze, Alliance for Primorska, Party of Slovenian Štajerska), and ethnic interests (e.g. the Alliance of Roma, Communita Italiana). Certain other contemporary issue‑oriented social movements of that period, such as the Greens of Slovenia, also evolved into parties.

2Out of these parties, the Democratic Opposition of Slovenia, also known as the DEMOS coalition, was created through an agreement between the Slovenian Democratic Union, the Social Democrat Alliance of Slovenia, the Slovene Christian Democrats, the Peasant Alliance and the Greens of Slovenia. In 1992 the Slovenian Democratic Union split into two parties: the social-liberal wing became the Democratic Party, and the conservative faction established the National Democratic Party. A third group, dissatisfied with both options, joined the Social Democratic Party (SDSS, later simplified to SDS), which suffered a clear defeat at the 1992 elections, barely securing its entry in the Parliament. Nevertheless, it formed a coalition with the winning Liberal Democracy of Slovenia and even became a member of the governing coalition. Later it became the dominant party of the right of center under the name of Slovenian Democratic Party.

3Only those socio-political organisations from the old regime that successfully transformed themselves, as well as new formations which managed to establish clear political identities and organisations, were able to survive the transition processes and constitute the new democratic party system. The successful parties generally managed to create a widespread organisation in the field, while at the same time maintaining a strong central party organisation and a high degree of party unity – all of this despite the lack of politically experienced members and with only limited financial resources. All other parties, including those with strong international support, vanished from the public life almost overnight.7

4In its first two decades, the party system of Slovenia was characterised by the relative openness, allowing for a relatively easy entry of new parties. However, at the same time it exhibited a high degree of party stability, with parties creating stable organisations, membership bases and political identities. At the level of interparty competition, the party system was initially characterised by the dominance of Liberal Democracy of Slovenia (LDS). This was followed by the increasing bipolarity, with one end dominated initially by the LDS and then a succession of three other, often new parties; while the other end has become increasingly dominated by the Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS).8

5Despite the relative openness of the Slovenian party system, only a small number of new parties entered the Slovenian Parliament in the first two decades. This trend started to change at the 2008 parliamentary elections, with the rapid decline of the LDS, strengthening of the SD as the temporary strongest party on the left, and the entry of a new party splintering from the LDS into the Parliament (Zares). At the 2011 and 2014 elections the instability of party systems reached new heights, with the once dominant LDS almost completely disappearing from the scene, being supplanted on the broad left first by the SD, then by the Positive Slovenia, and finally by the Miro Cerar's Party, later renamed as the Modern Centre Party. This opened a new trend of single-term parties, emerging and disappearing from one election to the next, leading to a huge turnover in the Parliament. Despite the increasing instability, no anti-system parties have emerged in Slovenia, although some parties have occasionally challenged the legitimacy of the ruling political elite and called for its replacement at early elections.9

6Generally we can state that political parties in Slovenia are not based on the representation and advocacy of narrow interests10 (e.g. individual social classes, interest groups, regions, etc...) and cannot be distinguished easily according to the standard understanding of the left and right wing, primarily based on the economic or social issues. For the most part, Slovenian parties aim to be "catch-all" organisations, as their programmes and appeals address a wide range of voters with varying concerns. This is also true in case of the rare parliamentary “interest-group parties” such as the DESUS. However, for the most of the time since multiparty democracy was established, the principal political parties did possess a clear political identity and identifiable, if not always permanently loyal, electoral base. Additionally, we should also note that in the past the parties which have shown a narrower focus on the specific issues and policies were not electorally successful in the long term, and the Green parties in the nineties are a typical example of this.

1.2. Legal and Financial Frameworks for a Transparent Functioning of Political Parties in Slovenia

1In accordance with the Political Parties Act, a political party in Slovenia is defined as "an association of citizens who pursue their political goals as adopted in the party's programme through the democratic formulation of the political will of the citizens and by proposing candidates for elections to the National Assembly, elections for the president of the republic and for elections to local community bodies."11 The Slovenian Constitution itself does not define neither political parties nor their functioning, but it provides for the individuals' right to freely associate with others, maintaining certain legal limitations on that right if required by the national security, public safety, and protection against the spread of infectious diseases. 12 Political parties are regulated by the Political Parties Act and the Elections and Referendum Campaign Act. A party may be founded by no less than 200 adult citizens of the Republic of Slovenia who sign a declaration on the founding of the party. A party becomes a legal entity and shall act in accordance with the Slovenian laws after the registration body (Ministry of the Interior) marks the application of a party (for the entry in the register) with the time and date when the application was received. Each party must add to the application for entry in the register a) 200 founding signatures, b) the party statute and its program, c) a record of the founding assembly, meeting or congress, naming the elected bodies of the parties and the office-holder who, in accordance with the statute, represents the party as the responsible person, d) a graphic representation of the symbol of the party.13

2In terms of internal democratic governance, all the main political parties must establish rules for the election of its leadership, the selection of candidates for elections, and the decision-making processes of the party’s programme platforms. There are also certain legal restrictions with regard to persons who cannot become party members or representatives in the leadership bodies of political parties. However, at the same time no demand for the public availability of the membership information is defined.14

3In terms of resources parties mostly rely on public funds, while privately provided funding has a smaller role. Legally, political parties in Slovenia can obtain funds from membership fees, contributions from private or legal persons, income from property, gifts, requests, the budget (national or local), and profit from the income of a company owned by it, but not from international funds or any type of domestic organisations with public ownership of at least 50 percent.15 The most frequent and most ‘welcome’ party financial contribution by far comes from the national budget. Parties that propose candidates for the elections to the National Assembly have the right to receive funds from the national budget, provided that they received at least 1 percent (or 1.2 % if two parties compete on a joint list; or 1.5 % if three or more compete together on one list) of votes nationwide. The amount of the public funds available to the political parties depends on the electoral result. It should also be noted that the political parties which are represented in the National Assembly are entitled to other "indirect" (financial, personnel, administrative) resources, which they receive from the National Assembly budget. It should be noted that although a 4-percent threshold is set at the national level as the level of eligibility for the reception of public funds, there are also some non-parliamentary parties – those which received more than one percent or less than four percent of the votes of voters at the national level – which are also entitled to public funding. In light of all of the above, in practice this means that Slovenian parliamentary parties receive a substantial portion of their resources from the budget (national and municipal), and only a moderate amount from membership fees and donations.

4However the issues with regard to the integrity of political parties, especially with regard to the transparency of party membership and funding, as well as issues related to the assurance of effective control over funding have been on the agenda almost constantly ever since the Slovenian independence. Political parties frequently, mostly on their own initiative, fail to inform the public about their membership, democratic governance procedures, as well as financial management. In light of the loose legal regulations, the general public therefore only has few limited possibilities to gain direct access to the information about the activities of the parties.16

5All these factors result in significant distrust towards political parties, facilitating the search for new but not actually innovative party choices in the increasing bipolarity of the multi-party system, maintained not only by the voters’ choices, but also through the media representation of the political parties and their actions.17

1.3. Parties in the Party System

1In the second half of 2015, there were 84 registered political parties in Slovenia, which is an increase from the 74 parties which were registered in 2012.18 Seven of these are represented in the National Assembly, which is about the average number of political parties represented in the National Assembly after the 1992 elections. So far, on average, one third of all parties competing in the elections have successfully entered the Parliament.19

2Regarding the number of party members in Slovenia we can only give a rough estimate, as it is very difficult to obtain credible information from the parties. According to some estimates,20 in 2008 108,000 people were members of political parties in Slovenia, which represents 6.26 percent of the Slovenian electorate. In comparison with the number in 1998, when members of the parties represented 9.86 percent of the electorate, in 2008 the membership in political parties decreased approximately by 3.5 percentage points.21

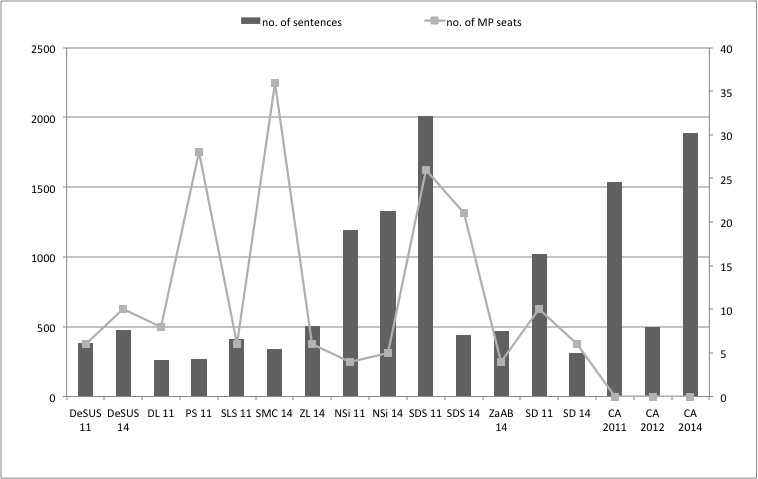

3If we compare the number of parties competing at the national parliamentary elections in Slovenia between 1990 and 2014, we can see that the aggregate numbers indicate a relatively stable dynamic of the party system, without dramatic changes in the numbers of parties competing in the elections, or parties entering the Parliament, and without significant changes in the government formula. Table 1 shows that the number of parties competing at the elections ranged from 17 to 23, reaching 26 only in 1992, after the departure of the DEMOS coalition from the political scene resulted in a large number of new parties contesting the elections. Throughout the period, except for the first elections, seven or eight parties were elected to the Parliament at all the elections.

4The number of parties in the governing coalitions ranged between two and five, but most of the time the government consisted of three or four parties. The patterns of governmental changes for the whole period of the Slovenian independence were characterised by the partial alternation of governing parties and partial changes in the government formula. Complete changes of governing parties were almost completely absent from the Slovenian party system, while innovations of the governmental formula mostly came about as the consequence of the emergence of new parties. In fact, the largest source of instability and volatility in the Slovenian party system has been the disappearance of old and emergence of new parties. This trend has become more important after the 2008 elections, given that the subsequent two elections resulted in completely new parties heading the government.

5Table 1 also indicates that at each of the elections since 1992 at least one new party was elected to the Parliament and at least two or three parties dropped from the Parliament. However, in some cases certain parties, such as New Slovenia (NSi) which failed to gain electoral representation at a certain point, managed to enter the Parliament on a later date.

6In the last decade the changes of the party system have picked up the pace. This was especially the case at the last two elections, held in 2011 and 2014, both of them called one year before the parliamentary term expired. At both of these elections two new and very successful political parties were established without being formed through a merger or secession from of one of the existing political parties. Conversely, before the 2011 elections most new parties came about mostly through splits or mergers of the existing political parties. The elections of 2011 and 2014 were also different because a few parliamentary parties existing from 1992 – two of them playing an important part in all the governments between 1992 and 2011 – failed to enter the Parliament. In 2011 the LDS and the only nationalistic party, the SNS, lost parliamentary representation, while in 2014 the oldest Slovenian political party, the Slovenian Peoples Party (SLS), failed to win any seats. These went to the winner of the 2011 elections Positive Slovenia (PS) as well as the newly established Citizens List (DLGV), which was the third biggest parliamentary party in the 2011–2014 term.

| 1990 | 1992 | 1996 | 2000 | 2004 | 2008 | 2011 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of candidates | 851 | 1475 | 1300 | 1007 | 1395 | 1182 | 1300 | na |

| No. of competing parties | 17 | 26 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 17 | 20 | 17 |

| No. of elected parties | 9 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| No. of newely elected parties | / | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2/3* |

| No. of unelected parties | / | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2/3** |

| No. of coalition parties | Demos, 5, later 6 | 4, later 3 and then 2 | 3 dropping to 2 | 5 dropping to 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 droping to 4 | 3 |

**Not counting the ZaAB as one of the successors to the PS

Source: National Electoral Commission (2015).

7Despite the frequent creation of new parties and elimination of existing parties, the Slovenian party system has been characterised by a relative stability. In the first decade of democratic politics, the Slovenian political arena was dominated by the Liberal Democracy of Slovenia (LDS), which controlled the government for 12 years after 1992 through coalitions that included left and right-wing parties alike. With the strengthening of the SDS, more clearly defined bloc alternatives emerged, and the last four elections were characterised by a bipolar pattern of competition between the SDS and a strong left-wing party: first the LDS, then the SD, PS, and now the Party of Modern Centre (SMC).

8So far the most important changes in the structure of the party system the last two elections, affecting predominantly the formerly dominant left and centre-left parties. In 2011 the LDS received slightly less than 2 % of votes, while its splinter party Zares, formed for the 2008 elections, also failed to enter the Parliament. The elimination of the only nationalist party, Slovene National Party (SNS), which had been a member of the Parliament since 1992, was significant as well. In 2011 the newly-established parties – the PS (centre-left) and the DLGV (centre-right)22 – gained seats and participated in the government, together receiving more than 37 percent of the votes. These parties soon dropped out of the Parliament in the 2014 elections, when they gained less than 4 percent of the votes in total. At the 2014 elections two new parties entered parliament: the Party of Miro Cerar, now renamed as the Modern Centre Party (SMC), and the United Left (ZL), together won more than 40 percent of the votes, while the 2011–2014 term parliamentary parties – the PS, DLGV and SLS – dropped out of the Parliament.

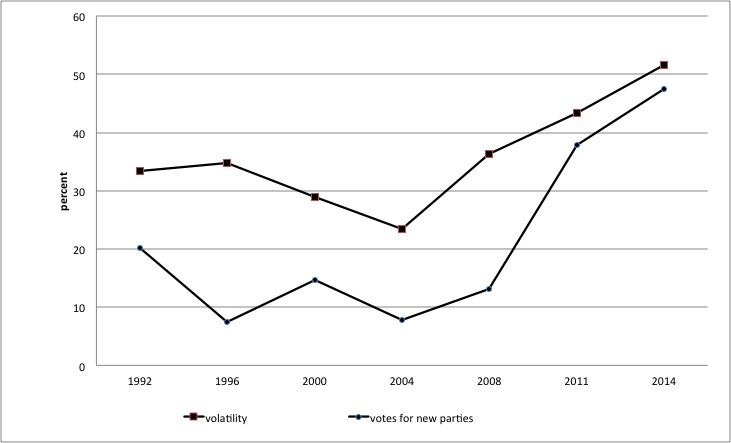

9When we shift our focus from the number of parties to the movement of voters, we can observe that the level of volatility at the Slovenian elections, as shown in Figure 1, remained comparatively high after the first elections (above 30 percent). However, in 2004 it dropped to 23 percent as a stronger bipolar pattern of party competition emerged. Since the 2008 elections volatility has been increasing again, topping 50 percent in 2014 and indicating a heightened instability of the party system as well as the weakening of links between the parties and voters and an increased willingness of voters to switch support between parties or move on to supporting an entirely new political party.

1Source: own calculations on the basis of the data provided by the National Electoral Commission (2015)

10If we analyse the share of votes for the new parties at each elections we get a somewhat better picture of what drives such high level of volatility over time. In Figure 1 above we can observe that both volatility and votes for new parties have increased significantly since 2008. Still, while volatility has been fairly high from the beginning, we can see that the vote share of the new parties was relatively modest until the 2008 elections, suggesting that volatility was mostly driven by the shifts of the electorate within the established parties. However, at last two elections the share of votes belonging to new parties has been on the rise precipitously, and this accounts for most of the volatility taking place in the Slovenian elections.

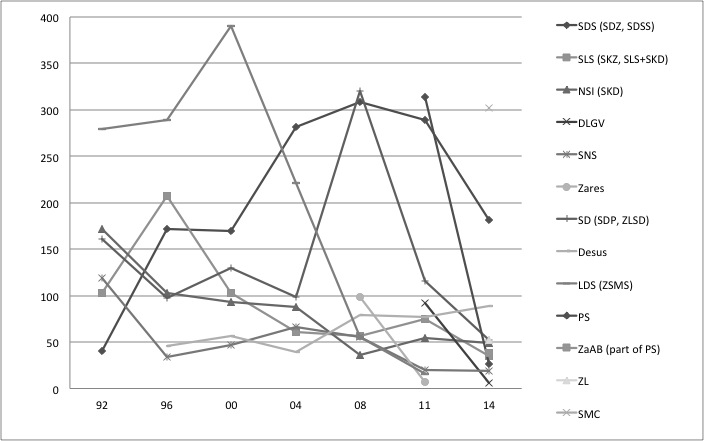

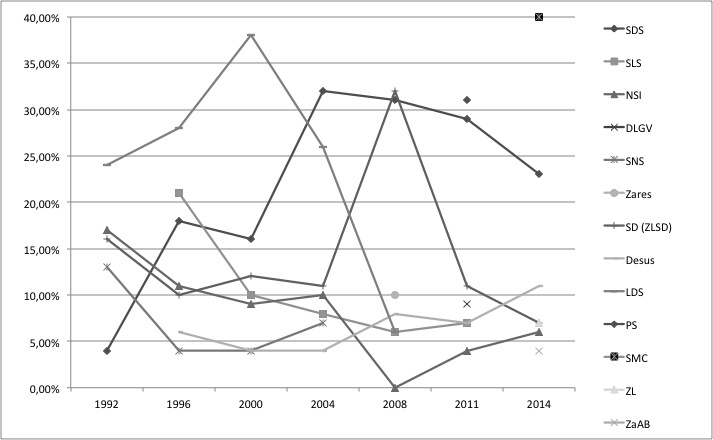

11When we look at the number of votes of the relevant parties in the period between 1992 and 2014, we see that the changes in the amount of party support were considerable, not only as far as the share of votes parties gained is concerned, but also with regard to the actual number of votes parties won at elections. What clearly comes across as the starkest finding is that with the end of the LDS dominance on the political scene, the voters supporting the broad left side of the political spectrum have shifted their support from the LDS to the SD, then to the PS, and finally to the SMC. On the right side, after the SLS lost the position of the second party in the party system at the 2000 elections, this consolidation took place primarily around the SDS in the second decade of democratic politics. The SDS managed to win the support of almost a third of the electorate between 2004 and 2011, only to witness the demobilization of about one third of its voters at the 2014 elections while still retaining the status of the second largest party in the context of the significantly reduced turnout.

12The seats in the National Assembly over time and in particular since 2000, are increasingly becoming distributed in such a way as to make a clear distinction between the smaller and larger parties in the context of an increasing bipolarity. In this context two principal parties control over 50 % of the seats, while the remaining five or six parliamentary parties distribute the remaining seats among themselves more or less evenly.

1Source: National Electoral Commission (2015).

1Source: National Electoral Commission (2014).

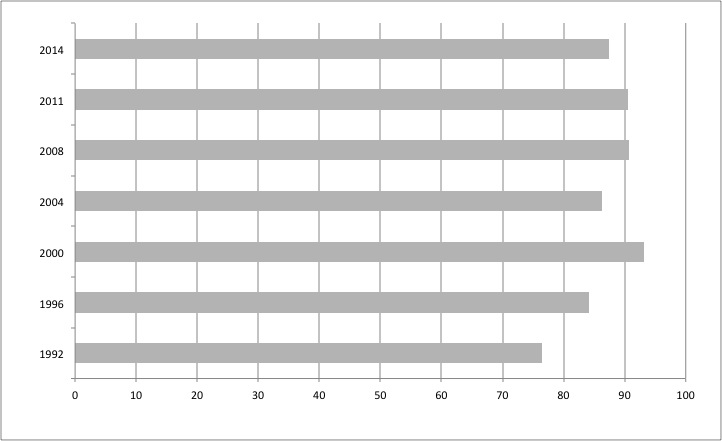

13Although the party system sees parties emerging and disappearing, for most of the period under consideration the electoral system has performed relatively efficiently in securing that the voters’ preferences have been represented and that votes have not been wasted. Since the establishment of the party system we have been able to observe that the share of voters who voted for parties represented in the Parliament, or, in other words, the share of voters whose votes are represented, increased just after the first elections. However, since then this share has remained between 84 percent and 93 percent within the period. The lowest share of represented voters (76 percent) can be traced back to the first elections in 1992, which are also the elections with the highest number of parties competing, while the best representation was achieved in 2000, when less than 10 percent of voters voted for parties that did not manage to enter the Parliament. The fact that despite the significant instability of the party system in the last decade 85 % of voters voted for parties that are represented in the Parliament is perhaps related to this very party system instability. As it happens, in the eyes of the voters such instability implies a reasonable probability that switching support to a different party will not result in a wasted vote. Furthermore, it also signifies that a large number of parties does not lead to a large number of wasted votes, or to a continued concentration of support for marginal parties.

1Source: National Electoral Commission (2014).

14In conclusion, when we observe the development of the Slovenian electoral and parliamentary party system, we can pinpoint several significant developments affecting the stability of the party system and changing the way it has functioned after the first decade of democracy:

- As a result of the 2004 elections, the first centre-right government, led by the SDS, was formed after the twelve-year dominance of the centre-left coalition government of LDS, leading to a more pronounced bipolarisation of the party system.

- In 2008 the centre-right government lost the elections. Once again a centre-left government was formed, with the SD (the former communist party) as the leader of the coalition with the DeSUS and two centre-left parties, the LDS and Zares, the parties that arose from the split of the LDS. The term of this government was characterised by the beginning of the economic slowdown and modest growth as well as increasing financial problems in the banking sector, as well as conflicts within the government. The term ended with the 2011 early elections effectively removing the SD from the position of the principal party of the centre-left.

- In 2011 early elections were held. The SDS and the newly formed Positive Slovenia won the most votes. The following three years were characterised by the changes of the government without elections and severe conflicts within the PS, the new DLGV, as well as within both governments in the 2011-2014 parliamentary term – one led by the SDS and the other by the PS.23 Both the PS and DLGV came into existence as alternatives to the existing established parliamentary parties, and both claimed to represent new agendas and boasted highly visible individuals as leaders in combination with relatively basic party organisations.24 This set in motion a new trend of one-shot parties, established by very prominent personalities shortly before the elections and without clear programme orientations, political identities or organisations, in order to be propelled into the government virtually overnight.

- A similar picture emerged in the second consecutive early elections in 2014, where the SMC repeated the Positive Slovenia's success from 2011, and the United Left (ZL), as a left-wing socialist alternative, entered the Parliament and extended the ideological scope of the political spectrum on the left. On the right end of the political spectrum, the oldest Slovenian party SLS dropped out of the Parliament. The same happened to the Civic List (DLGV), which entered the Parliament only in 2011 and reduced the number of the political actors right of center.

1.4. Parties and the Public Opinion

1The significant instability of the party system in the last decade, in comparison with the first decade of democratic politics, may indicate that the public attitudes towards political parties may be changing as well. If this is the case, it can be expected that other political institutions could be affected as well. The fact that some political parties are losing support and disappearing while others are rising without clear programmes, party identities or organisation may indicate that the voters feel a certain degree of dissatisfaction with the parties.

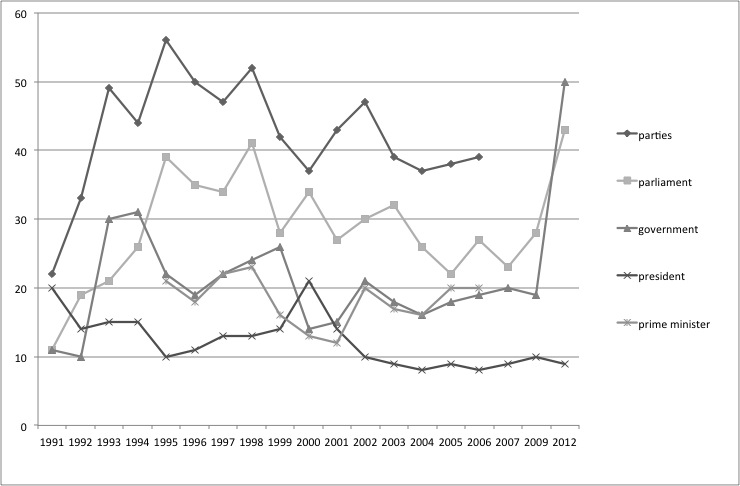

2This is confirmed if we look at the level of the public support for the political parties and political institutions through which the parties operate. The public image of the political parties and the National Assembly as the principal arena of their institutional activities is fairly low in Slovenia. Regarding the central government political institutions as well as some other societal institutions, the political parties and the National Assembly are consistently assessed by the respondents as the least trustworthy. The public opinion survey polls (called Polibarometer) in 201025 revealed that only three percent of respondents trusted the political parties, while as much as 64 percent did not trust them. According to a study carried out in March 2011,26 the level of trust was even lower – only two percent of respondents trusted the political parties, while distrust increased to 68 percent. Such considerable (and increasing) rate of distrust in the parties is also a result of the increasing perception of the clientelistic relationships between the parties and various interest groups as reported by the various media.27

3While the parties suffered from the lack of trust by the public since the middle of the 1990s, over the last few years the trust in the government and the Parliament has declined significantly as well. The timing of this development closely coincides with the economic crisis affecting the country. However, it also coincides with the increase in volatility of the electorate and the increased turnover, or emergence and disappearance of political parties from one election to the next. All of this indicates that the public opinion sees political parties as institutions that fail to fulfil their function, and their failure is affecting the attitude of voters towards the whole political system.

1Source: Niko Toš et. al., Politbarometer 3/2011 and 1/2012. Meritve v času izrednih parlamentarnih volitev v DZ RS oktober 2011 – januar 2012 [dataset] (Ljubljana: Public Opinion and Mass Communication Research Centre, 2012)

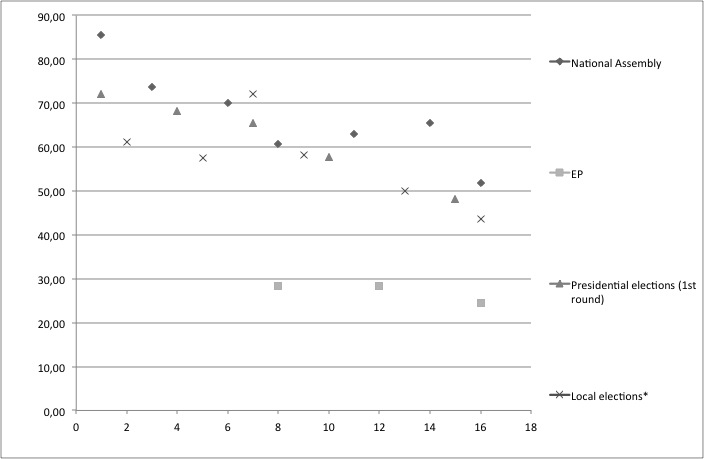

4Electoral participation in the elections at various levels is a further sign of the shift in the popular attitudes towards the political system. Figure 3 shows a considerable decline in the electoral turnout since the 1992 elections, signifying a changing attitude of the public towards the elected institutions. In 1992 the turnout at the parliamentary elections was 85 percent. In 1996 and 2000 it dropped to just above 70 percent, only to fall to only 60 percent in 2004. The turnout remained between 60 and 65 percent until 2014, when it dropped to 51 %, which is one of the lowest levels in Europe for national elections. Similar trends are evident also for the presidential and local elections, where the turnout (initially at a lower level than in the case of parliamentary elections) was declining in accordance with the trends at the national elections. The level of turnout was the lowest for the European Parliament elections, as it did not exceed 30 percent in any of the three European Parliament elections so far.

1Source: National Electoral Commission (2015).

Legend: * due to the legislative changes, in a certain period the local elections were not called for all the local communities at the same time, which makes the collection of turnout data for the local elections turnout more challenging for the terms under consideration, although this does not have any direct impact on the turnout interpretations for the purposes of this paper.1.5. Party Identification and Preferences

1The comparative analysis of the relationship between the ideological positioning of voters and political parties in Slovenia, with respect to their position on the political spectrum, has so far shown that the classic economic left-right position in Slovenia is one of the least relevant factors of electoral choice.28 Instead, most studies reveal that the main ideological division in Slovenia revolves around the interpretation of history, and in that context primarily around the interpretation of the political divisions during World War II, the interpretation of the nature of war and its participants in Slovenia, as well as the character of the post-war state and the events related to it.29 The issues of the traditional versus modern attitudes and values regarding individual freedom, role of family, religion and morality, as well as the definition of national identity are closely related to these historical divisions. These elements have formed another dimension of the dominant symbolic division.

2What appears to characterise the social foundations of the Slovenian party system is a stable distribution of the voters' party identification across the political spectrum, with somewhat lesser stability of party identity in case of the left-wing voters. Furthermore, we cannot observe any consistent classic ideological divisions based on the socio-economic differences, despite the issue of the role of the old and new economic and social elites. The interpretation of history, attitude towards the communist regime and other similar issues form a very clear symbolic division. This dominance of symbolic politics means that with respect to economic issues, parties sometimes behave in a way which is not likely to be consistent with their overall ideological orientation.30

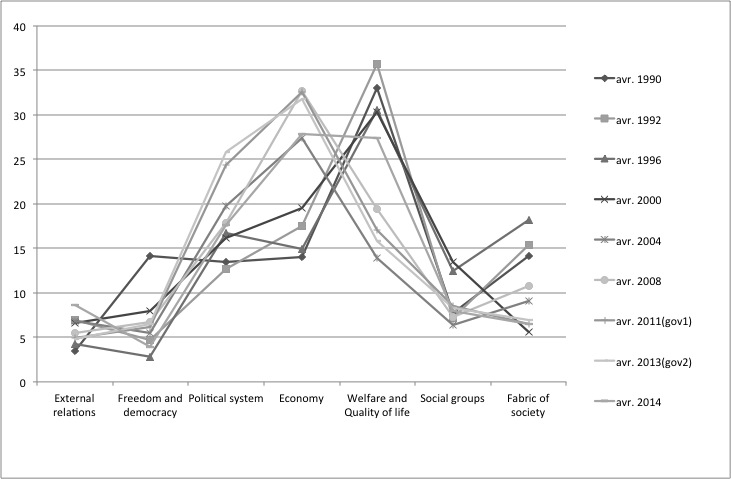

3The analysis of the Slovenian parties’ electoral programmes reveals that the character of party competition is in some respects typical of the electoral politics in other Central and Eastern European countries with respect to the scope and type of the prevailing policy issues.31 Moreover, it is apparent that the contemporary Slovenian political parties are not formed as representatives of narrow interests, but rather that they have a position of so-called "catch-all" parties, as their programmes address a wide range of voters, even when they are nominally representing particular social groups, like the DeSUS.

1Sources: own data and calculations on the dateset methodology by Hans-Dieter Klingemann, Andrea Volkens, Judith Bara, Ian Budge, Mapping policy preferences II: estimates for parties, electors, and governments in Eastern Europe, European Union, and OECD 1990-2003 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006); Simona Kustec Lipicer and Samo Kropivnik. "Dimensions of Party Electoral Programs: Slovenian Experience," Journal of Comparative Politics 4.1 (2011): 52

4The data shows that the Slovenian parties, in general, keep the contents of their programmes increasingly stable over time, despite the significant contextual changes in the society and economy over the last decade. The priority given to particular issues in the party programmes has been changing over time, but generally, welfare and quality of life issues have topped the list, while the economic issues have grown in importance over time, mostly at the expense of the decline in the priority of welfare issues as well as all the issues related to social policy. This shift is more obvious in the case of the leading centre-right Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS), where we can observe a sharp shift of focus between the two periods. A less prominent but still obvious shift took place in the programmes of other parties, where we observe slow, gradual changes leading to a shift in the policy orientation.32 It is reasonable to speculate that these changes have appeared mostly as a result of the ongoing external social, economic and political turbulences, manifesting themselves in the local context. Apart from the shifts in focus, we can observe that the structures of party programmes have become more similar over time with respect to the structure of the issues included in the party programmes.33

5A further analysis of the 2004-2011 period reveals that the structural differences in issue priorities clearly separate the parliamentary from the non-parliamentary parties rather than, as already indicated, along the lines between the left vs. right or government vs. opposition.34 Parliamentary parties are more focused on the political system and economy, while non-parliamentary parties prioritise welfare, quality of life, and social fabric. These differences are expected and correspond to the findings of the general policy analyses. They imply that non-parliamentary parties are much more issue-oriented and focus on the policies related to the welfare and/or societal issues than the leading parliamentary parties are far more catch-all oriented and focus on the fundamental issues of the political system. On the other hand, there are no obvious differences in the issue structure between the more and less successful parliamentary parties. The only exception, to a degree, to the general trend shown in Figure 7 seems to emerge in 2014, where the issue dimensions are more evenly represented in the party programmes in comparison with the previous elections.

1Sources: own data and calculations; Simona Kustec Lipicer and Niko Toš, "Analiza volilnega vedenja in izbir na prvih predčasnih volitvah u državni zbor," Teorija in praksa 50, no. 3/4 (2013): 503

6Furthermore, even the new parties (PS and DLGV, SMC or ZL), which ran at the 2011 and 2014 elections with atypically short and general programmes but nevertheless experienced significant electoral success, are close to the other parliamentary parties as far as the issue structure of their party programmes is concerned. This may point to the conclusion that the electoral upheaval, affecting Slovenian politics at the 2011 and 2014 elections, was not so much about the voters trying to find a new political direction, but rather that it was a case of the voters being dissatisfied with the old political elites, therefore trying to replace them with a new set of actors without asking for credentials or assurances that the new elites in fact have any new solutions to the problems.

1.6. Final remarks

1The Slovenian party system as an integral element of parliamentary democracy since the Slovenian transition to democracy has exhibited several significant trends. On one hand the party system has exhibited a significant degree of stability in its aggregate characteristics. The number of parties competing at elections as well as the number of elected and governing parties, the broad contours of party programmes, and the patterns of governmental alterations have remained broadly stable over time.

2At the same time, while the party system has exhibited a significant degree of stability at the aggregate level, over time the instability at the level of political parties has increased. This has taken place in the context of the increased dissatisfaction of the citizens with the political parties. Electoral volatility, always high, further increased dramatically at the 2011 and 2014 elections, when the old parties were eliminated from the government from one election to the next and the share of votes for new parties reached 40 % or more. Increased volatility is just one of the trends indicating the increasingly critical attitude of citizens towards the parties and political institutions most closely related to the political parties, such as the government and the Parliament. It remains to be seen whether such a critical attitude of citizens towards the political parties will continue in the next electoral cycle. However, it is evident from the developments in the last few years that the new parties have a number of weaknesses and lack the resilience that the old parties have in terms of stable links with voters, stable party organisations allowing for steady and effective patterns of political recruitment, and stable party identity. The new parties that emerged in the 2014 elections are vulnerable the same as were their predecessors in 2011, and it is not unlikely that the degree of instability will persist, though the external pressure on the party system might decline if the economic conditions and modes of transparent governance are stabilised.

3Finally, the party system is an essential element of the parliamentary system. Parties are the principal conduit for the recruitment of political elites and representation of the political preferences of voters. It is therefore not unlikely that the changes in the party system could ultimately lead to changes in the parliamentary arena.

* Associate Professor and researcher, PhD, Faculty of Social sciences, University of Ljubljana, Kardeljeva pl. 5, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia, simona.kustec-lipicer@fdv.uni-lj.si

** Assistant Professor, PhD, Faculty of Political Sciences, University of Zagreb, Lepušićeva ul. 6, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia, ahenjak@fpzg.hr

1. Niko Toš and Vlado Miheljak, "Transition in Slovenia: Towards Democratization and the Attainment of Sovereignty," in Slovenia Between continuity and change 1990–1997, ed. Niko Toš and Vlado Miheljak (Berlin: Sigma, 2002).

2. Samuel P. Huntington, The Third Wave: Democratization in the late twentieth century (London: Univeristy of Oklahoma Press, 1991).

3. Juan Linz, "The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes: Crisis," in Breakdown and Reequilibration, ed. Juan Linz and Alfred Stepan (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1978).

4. Danica Fink-Hafner, "Between continuity and change," in Slovenia Between Continuity and Change 1990–1997, ed. Niko Toš and Vlado Miheljak (Berlin: Sigma, 2002).

5. Ibid., 43.

6. Janko Prunk, "Politično življenje v samostojni Sloveniji," in Dvajset let slovenske države, ed. Janko Prunk and Tomaž Deželan (Maribor: Aristej; Ljubljana: Fakulteta za družbene vede, Center za politološke raziskave, Ljubljana 2012), 17–57.

7. Fink-Hafner, "Between continuity and change," 48.

8. For more information about the characteristics of the Slovenian political parties since 1990 see Danica Fink-Hafner, "Strankarski sistem v Sloveniji: Od prikrite k transparentni bipolarnosti," in Političke stranke i birači u državama bivše Jugoslavije, ed. Zoran Lutovac (Beograd: Friderich Ebert Stiftung, 2006), 363–384. Danica Fink-Hafner, "Slovenia: Between Bipolarity and Broad Coalition-Building," in Post-Communist EU Member States: Parties and Party Systems, ed. Susanne Jungerstam-Mulders (Aldershot, Burlington: Ashgate, 2006), 203–231.

9. Jure Gašparič, Državni zbor 1992-2012: o slovenskem parlamentarizmu (Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2012). Danica Fink-Hafner, Damjan Lajh and Alenka Krašovec, Politika na območju nekdanje Jugoslavije (Ljubljana: Fakulteta za družbene vede, 2005).

10. In contrast to most EU countries, "actual" Eurosceptic parties cannot be detected in Slovenia. In the period of the Slovenian integration into the EU the parliamentary Slovenian National Party was characterised as a "Eurosceptic" party. However, during, for example, the campaign for the referendum on the Slovenian accession to the EU it remained completely inactive and inconspicuous.

11. "Political Party Act. Official consolidated text," Official Gazette of the RS, no. 100 (2005): art. 1.

12. Constitution of the Republic of Slovenia, art. 42.

13. Ibid., art. 8.

14. "Political Party Act. Official consolidated text," Official Gazette of the RS, no. 100 (2005).

15. "Political Party Act. Official consolidated text," Official Gazette of the RS, no. 100 (2005): art. 21 and 26. See also Article 22 for certain criteria and limitations that are set for obtaining the stated for the acquisition of the relevant eligible funds.

16. Supervision is carried out by the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Finance, while financial auditing control is assured by the Court of Audit. For more information see also "Political Party Act. Official consolidated text," Official Gazette of the RS, no. 100 (2005): art. 27–29.

17. For media reports see: Delo, accessed December 3, 2015, www.delo.si. Dnevnik, accessed December 3, 2015, www.dnevnik.si. Večer, accessed December 3, 2015, www.vecer.si. Prvi interaktivni multimedijski portal, MMC RTV Slovenija, accessed December 3, 2015, www.rtvslo.si. Planet Siol.net, accessed December 3, 2015, www.siol.net. MLADINA.si , accessed December 3, 2015, www.mladina.si. Revija Reporter, accessed December 3, 2015, www.reporter.si. Tednik Demokracija, accessed December 3, 2015, www.demokracija.si. See also Greco country monitoring reports at: Untitled 1, accessed December 3, 2015, http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/monitoring/greco/default_en.asp.

18. Ministry of Interior, Political Party Register, at Društva, politične stranke in ustanove - objave na spletu, http://mrrsp.gov.si/rdruobjave/ps/index.faces.

19. No. of all competeing parties in the period 1992–2014, divided with the number of parties, elected in the Parliamnet in the period 1992–2014.

20. Ingrid van Biezen, Peter Mair and Thomas Poguntke, "Going, Going…Gone? Party Membership in the 21st Century," paper prepared for the workshop on ‘Political Parties and Civil Society’, ECPR Joint Sessions, Lisbon, April 2009.

21. Ibid.

22. Simona Kustec Lipicer and Niko Toš, "Analiza volilnega vedenja in izbir na prvih predčasnih volitvah v državni zbor," Teorija in praksa 50, no. 3/4 (2013): 503.

23. On 20 September 2011 the vote of no confidence was passed in the Parliament. On 21 October 2011 the President of the Republic dismissed the Parliament and called for elections. The elections were held on 4th December 2011. On 22 October 2011 Zoran Janković, the mayor of the Slovenian capital of Ljubljana, established the Zoran Janković List - Positive Slovenija party, which won the 2011 parliamentary elections with 28.51 % of votes and became the leading parliamentary opposition party. Gregor Virant as one of the lieutenants of the SDS party leader Janez Janša, also the Minister of Public Administration in Janša's 2004-2008 government, resigned from the SDS in late summer of 2011 and established a new party, the Gregor Virant's Civic List, on 21 October 2011. His list won 8.37 % of votes and became one of the government coalition parties.

24. See for example Krašovec and Tim Haughton, "Europe and the Parliamentary Elections in Slovenia December 2011," EPERN Election Briefing 69 (2012).

25. Survey Politbarometer 12/2010 (Ljubljana: Center za raziskovanje javnega mnenja, 2010).

26. Survey Politbarometer 03/2011 (Ljubljana: Center za raziskovanje javnega mnenja, 2011).

27. Data available in various media presses: Delo, www.delo.si. Dnevnik, www.dnevnik.si. Večer, www.vecer.si. Prvi interaktivni multimedijski portal, MMC RTV Slovenija, www.rtvslo.si. Planet Siol.net, www.siol.net. MLADINA.si, www.mladina.si, Revija Reporter, www.reporter.si. Tednik Demokracija, www.demokracija.si.

28. Russell J Dalton, David M. Farrell and Ian McAllister, Political Parties and Democratic Linkage: How parties organize democracy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

29. Hans-Dieter Klingemann, Dieter Fuchs and Jan Zielonka, Democracy and Political Culture in Eastern Europe (London: Routledge, 2006). Drago Zajc and Tomaz Boh, "10. Slovenia," in The Handbook of Political Change in Eastern Europe, ed. Sten Berglund (Cheltenham, Northampton (MA): Edward Elgar Publishing, 2004). Danica Fink-Hafner and Alenka Krašovec, "Europeanisation of the Slovenian party system–from marginal European impacts to the domestication of EU policy issues?" Politics (2006).

30. Russell J Dalton, David M. Farrell and Ian McAllister, "The Dynamics of Political Representation," in How Democracy Works: Political Representation and Policy Congruence in Modern Societies, ed. Martin Rosema, Kees Aarts and Bas Denters (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011). Samo Kropivnik and Simona Kustec Lipicer, "Party Manifestos in Slovenia," Prepared for delivery at the 2012 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, August 30 – September 2, 2012.

31. Hans-Dieter Klingemann, Andrea Volkens, Judith Bara, Ian Budge, Mapping policy preferences II: estimates for parties, electors, and governments in Eastern Europe, European Union, and OECD 1990–2003 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006). According to the applied methodology, the scope of electoral program issues is analyzed by measuring the frequency of the following seven domains in each program 1) External Relations; 2) Freedom and Democracy; 3) Political System; 4) Economy; 5) Welfare and Quality of life; 6) Fabric of Society; 7) Social Groups.

32. Including also a unique and very strong focus on the political system issues.

33. More on this in: Simona Kustec Lipicer and Samo Kropivnik, "Dimensions of Party Electoral Programmes: Slovenian Experience," Journal of Comparative Politics 4.1 (2011): 52.

34. Ibid.